As an arts student at the Villa Arson in Nice (France) in the early 1980s, Ghada Amer became acutely aware of the fact that the history of art, and that of abstract painting in particular, was a history of masculine art. Women were absent from the art history books. They were absent also from the classes her teachers taught. In fact, female students were discouraged, if not actively shunned, from studying painting in art school. There was no future for women in painting, as her (male) teachers kept repeating.

This experience marks the beginning of Ghada Amer’s artistic trajectory as a painter. As a budding female painter. Ghada Amer was determined to rewrite the history of art, to claim a place in it, and to (re)-instate women permanently in it.

For me, the choice to be mainly a painter and to use the codes of abstract painting, as they have been defined historically, is not only an artistic challenge: its main objective is to occupy a territory that has been denied women historically. I want to occupy this territory aesthetically and politically by creating materially abstract paintings. In addition, I want to integrate within this male field a feminine universe: one of sewing and of embroidery. By hybridizing these two worlds, the masculine and the feminine, the canvas becomes a new territory where the feminine has its own place in a field dominated by men, and from where, I hope, we won’t be removed again.

Ghada Amer

Painting as a woman 1: Domesticity

How to Speak about women as a woman artist?

Choosing to Embroider

Ghada Amer was shaped and nourished by the history of (male) painting. While holding firmly onto that tradition, she inserts into it a medium long deployed by feminist artists since the 1970s as a political tool, a craft long associated with women: embroidery. By layering thus a mode of feminine writing (embroidery, sewing, needle and thread) over the traditional male medium par excellence (painting, brushes), she positions women within the history of art and the history of painting.

Her earliest artistic productions boldly position embroidery and sewing on stretched canvases hanging on the white walls of galleries and museums, that is in the very space traditionally reserved for male painters. By combining the masculine language of painting with the female language of embroidery, Ghada Amer gives birth to a new alphabet of an expansive visual language that she will spend her entire life refining.

Embroidery on canvas becomes henceforth her signature formal strategy. At the very first, her embroidery was reduced to its simplest form: neat outlines of the figures.

Painting Women as Domestic workers

Ghada Amer’s preferred subject matter are women. In the early 1990s, She embroidered primarily women engaged in domestic activities.

Cinq femmes au travail (1991)

Ghada Amer’s “Cinq femmes au travail” (1991) can be considered her first artistic manifesto and has wide relevance for her entire artistic career.

This work is made up of four canvases, each outlining in red thread a woman engaged in a stereotypical domestic activity: ironing, grocery shopping, mothering, vacuuming.

The viewer cannot help but wonder who and where the fifth woman mentioned in the title may be. The answer of course is that the fifth woman, not represented physically here, is the female artist herself, Ghada Amer who is invisible, yet who is engaged in both embroidering and in becoming an artist. She is the director of a new symphony orchestra.

Ghada Amer became quickly dissatisfied with what she viewed as the alignment between her chosen medium and her imagery, that is between form and content, between embroidery the representation of domestic women. She sought to challenge the double submission of the women that she had created, of women who embroidered the representation of their own alienation. The artist wanted to create dissonance where she had till now created only alignment.

Painting as a woman 2: Inventing a new abstract visual language

Erotic vs. Pornographic

In her quest for a new subject to paint and embroider on her canvases, one that would sharply contrast with the medium of embroidery, yet be representative of all women, Ghada Amer turned to a most unlikely source: porn magazines. In them, the artist found images of prostitutes, of women who unashamedly claimed their own sexual pleasure.

Ghada Amer’s earliest painting featuring this new porn subject is tellingly entitled “Sans Titre (La Première)” (Untitled (The First one) (1992).

Rather than being confined by domestic chores, like the previous women in the Domestic series, the new porn star in Ghada Amer’s new series is someone who relishes in her own sexual pleasure. She is no longer a simple object of the male gaze and his desire but rather a subject who produces her own pleasure.

Sexuality becomes henceforth for the artist an endless reservoir for the representation of female empowerment and a way of bringing to the fore the subject matter of female desire and sexual pleasure, both taboo topics throughout the world.

I looked at pornographic magazines because they showed the contrary of the submissive woman. I liked the idea of shifting imagery from the docile woman to the liberated prostitute.

Ghada Amer

Though Ghada Amer appropriates her imagery from publications classified as pornography,

she refuses the portrayal of her paintings as “pornographic,” a categorization often used to either sensationalize or dismiss her work.

I find the difference between the erotic and the pornographic to be really problematic. I noticed that when we want to dismiss the erotic, we call it pornographic. It’s very moralistic. I don’t find my work pornographic because it is not moralistic.

Ghada Amer

Far from being interested in the actual representation of women in the pornography magazines or even on her own canvases, Ghada Amer’s primary interest is not the subject matter per se, but rather in painting and the repositioning of the (woman) artist in the history of art.

For Ghada Amer, indeed:

The content is not the girls, the content is the painting itself.

Erotic vs. Pornographic

Ghada Amer endeavors to create a new visual language, one that goes well beyond the neat outlines of her Domestic series. As her figures become more expressive around 1993, her canvases acquire more texturality. If little paint appeared on her canvases at the time, colored thread itself emerges as a new kind of painting.

The texturality of her paintings is achieved through a very precise layering of acrylic paint, embroidery, and gel medium, a technique that has since become her signature composition.

The gel medium is applied to each canvas only once the paint is dried and the embroidery completed. Standing in front of the canvas hanging vertically on the wall of her studio, Ghada Amer combs through the loose ends of the thread with one hand before fixing them on the canvas with the gel medium. Once dry, the cascading lines of the thread are set/glued onto the canvas and result in what Ghada Amer refers to as her “drips”.

The drips are thus a formal strategy intended to add a painterly quality to the thread. Although the imagery Ghada Amer utilizes is representational (women from porn magazines), the drips largely (un)intentionally obscure the erotic images that are embroidered. Viewers are often teased into playing hide and seek with each of Ghada Amer’s paintings. They are caught trying to tease out the figures from underneath the layers of thread, of loops and lines that are glued on the canvas, a playful experience of peekaboo, of presence and absence, of visibility and invisibility.

Once again, Ghada Amer’s use of embroidery is intended as an artistic language that is both opposed to and in dialogue with painting. Unlike paint, the very use of thread allows the artist to work directly with and through the figures. It is a medium that blurs the boundary between object and painting, craft and art, and that interrupts immediate identification of her subject matter. By interfering with a linear reading or interpretation of her works. Ghada Amer invites the viewer to stop and think, thus inscribing her production within the history of abstract expressionism.

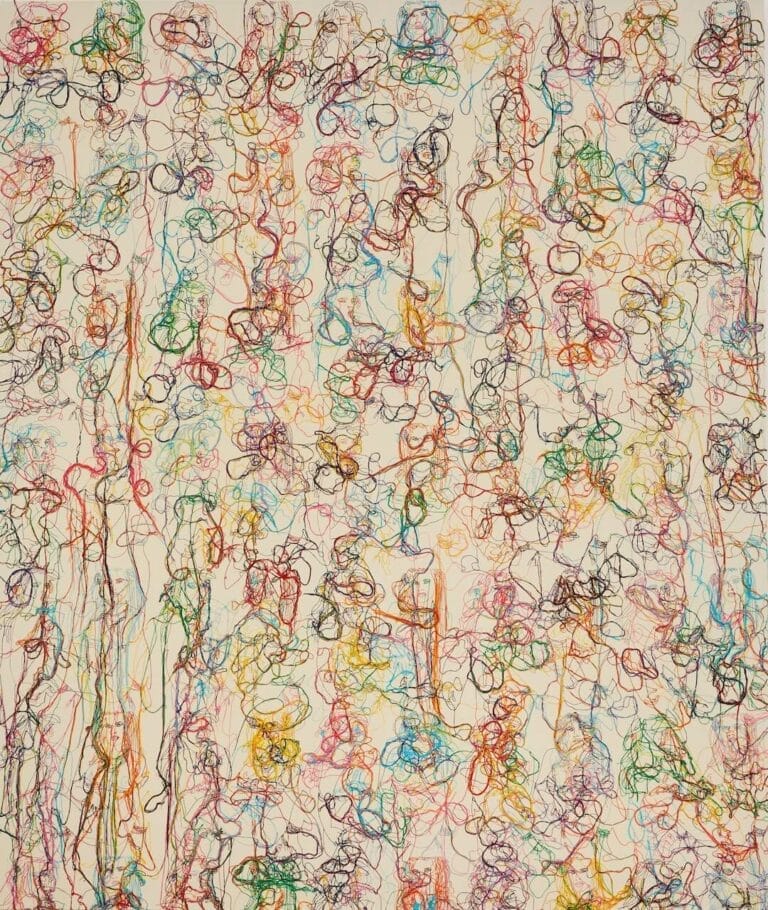

Color Misbehavior (2009)

Ghada Amer’s embroidered paintings deliberately recall those of Abstract Expressionism from afar – a nod to the prominent movement dominated by men and to the various formal strategies they are associated with, most notably expressive strokes, dripped paint, monochromes, and the grid.

In fact, some of Ghada Amer’s titles evoke directly a number of major male canonical painters and position the artist (as a woman) within a history of art that has excluded women for far too long.

In this regard, Ghada Amer’s “The Turkish Bath” (2006) is a nod to Ingres’ painting of the same title, while her Nympheas series (2011, 2018) are obviously a homage to Monet’s paintings of the same title. The new Albers (2002), like her Grids series, are Ghada Amer’s feminine and feminist version of Frank Stella’s symbols of rationality and order or of Josef Albers’s geometric abstraction works. If her Drips series remind us of Jackson Pollok, her Monochromes (Another Black Painting, Lady in Pink, White) evidently remind us of absolute abstraction, as in the various types of monochrome art created by Kazimir Malevitch, and of minimalism and conceptual art. And of course, one can discover many other references to master painters from the past whether explicitly referenced or not (Matisse and Fernand Léger among others).

From the Drips to the Big Bang

The development of Ghada Amer’s new visual language reaches its pinnacle with Color Misbehavior (2009), a work that is, for the artist, as important as her first painting, “Cinq femmes au travail” (1991).

It was only when I finished Color Misbehavior (2009) that I suddenly felt that I could actually paint after all these years. This painting is as important to me as my first work, Cinq femmes au travail, 1991. When I did that painting in the early 1990s, I knew I was developing the language of thread. With Color Misbehavior, produced some twenty years later, I discovered that I could actually paint gesturally with thread. While I had been developing a language and a grammar, I was now able to write full sentences. Gradually the subject matter of my painting has become less important to me. Yes, they are still porn women, but I am more interested in the actual technique now.

Ghada Amer

Over the years, Amer has continued to develop the language and thus the technique of her “drips.” In 2009, she initiated a new practice for arranging the excess threads upon the surface of her canvases. Rather than positioning herself vertically across from her work to comb through the loose threads and apply the gel medium, Ghada Amer places the embroidered canvas horizontally, face down. She lies beneath it, carefully combing the loose threads and undoing any tangles until all the threads hang perfectly. She then emerges from underneath the canvas, holds it firmly horizontally before letting it drop to the floor, letting the wind and pure chance define the shape of the threads which she then proceeds to fix with the gel. This is the birth of her Big Bang series (2010-2011). With this new process, Ghada Amer points out: “It’s the whole canvas that is actually making the paining, not my brush.”